The toll of nuclear war would be instantly catastrophic for those who are within the immediate path of the weapons. But a new study shows just how deadly the scope of such a war would be.

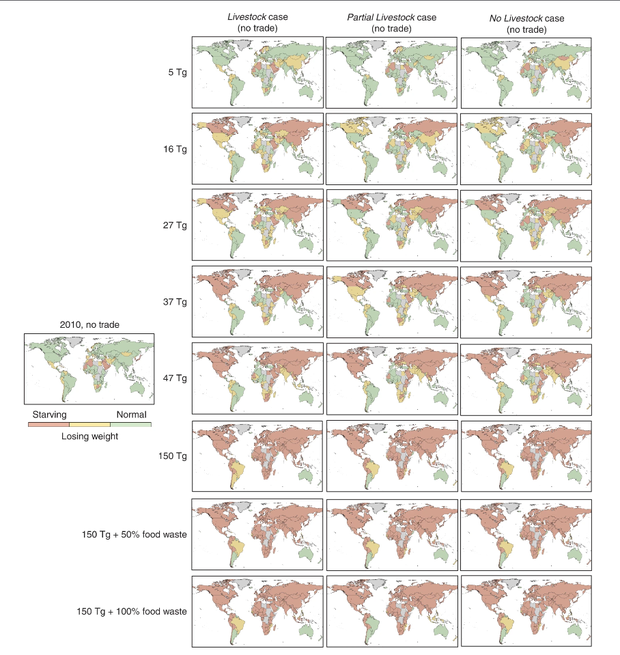

A nuclear blast would cause worldwide famine, according to the study, published in Nature Food on Monday, as massive amounts of soot would block sunlight, disrupt climate systems and limit food production. "[It] would be a global catastrophe for food security," the authors said.

The toll of nuclear war would be instantly catastrophic for those who are within the immediate path of the weapons. But a new study shows just how deadly the scope of such a war would be.

A nuclear blast would cause worldwide famine, according to the study, published in Nature Food on Monday, as massive amounts of soot would block sunlight, disrupt climate systems and limit food production. "[It] would be a global catastrophe for food security," the authors said.

Ad Code

Search This Blog

Cambodia News

Nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia would kill more than 5 billion people – just from starvation, study finds

Cambodia - Khmer

August 17, 2022

The toll of nuclear war would be instantly catastrophic for those who are within the immediate path of the weapons. But a new study shows just how deadly the scope of such a war would be.

A nuclear blast would cause worldwide famine, according to the study, published in Nature Food on Monday, as massive amounts of soot would block sunlight, disrupt climate systems and limit food production. "[It] would be a global catastrophe for food security," the authors said.

The toll of nuclear war would be instantly catastrophic for those who are within the immediate path of the weapons. But a new study shows just how deadly the scope of such a war would be.

A nuclear blast would cause worldwide famine, according to the study, published in Nature Food on Monday, as massive amounts of soot would block sunlight, disrupt climate systems and limit food production. "[It] would be a global catastrophe for food security," the authors said.

Popular Posts

ប្រវត្តិស្រែអំបិលមានតែខេត្តកំពត និងកែប

January 12, 2015

ប្រទេសក្រូអាស៊ី ជ្រើសរើសប្រធានាធិបតីស្រីលើកដំបូងបង្អស់

January 12, 2015

ទស្សនៈ ៖ មាត់ត្រីកំភ្លាញ

October 11, 2015

រាជរដ្ឋាភិបាលគ្រោងចំណាយ ៦,៧ ពាន់លានដុល្លារសម្រាប់ឆ្នាំ ២០១៩

October 26, 2018

អូស្ត្រាលីស្វែងរកការហាមឃាត់សាលារៀនពីការបណ្តេញសិស្សភេទទីបី

October 13, 2018

Labels

- 1MDB (2)

- 2022FIFAWorldCup (1)

- 2022MINI (1)

- 2022Volkswagen (1)

- 2023AsianCup (1)

- 2036Olympics (1)

- 5G (1)

- 5G phone (1)

- ABA (2)

- ABABank (1)

- Abbott (1)

- Abe (3)

- abortion (3)

- AbrahamLincoln (1)

- AbrahamLincolncarrier (1)

- Abramovich (2)

- Abramstank (1)

- AbuDhabi (1)

- abuse (5)

- Academics (1)

- ACCC (1)

- accident (2)

- Accidents (28)

- Accidents Maritime (1)

- AccidentsMaritime (8)

- AccidentsTraffic (8)

- AccidentsWorkplace (2)

- Accor (1)

- Acidattack (1)

- Acleda (5)

- Acleda Bank (1)

- AcledaBank (5)

- AcledaMobile (1)

- AcledaQR (1)

- Acquisitions (2)

- activists (13)

- actor (2)

- actress (1)

- ADB (6)

- ADHD (1)

- Adidas (1)

- AdolfHitler (1)

- adoption (2)

- Advertisements (1)

- AEON (1)

- AeonMallSenSok (1)

- Aerospace (7)

- AFF (1)

- Afghanistan (19)

- Africa (7)

- Africanswinefever (2)

- Ageing (2)

- AGREEMENT (2)

- AgriBee (1)

- agricultural (1)

- agriculturalproduct (1)

- Agriculture (2)

- Agricultureandfarming (20)

- agricultureproduct (1)

- agriculturesector (2)

- AHA Central (1)

- AI (7)

- AidsHIV (1)

- Air travel (2)

- AirAsia (5)

- Airbnb (2)

- Airbus (2)

- aircraftcarriers (6)

- Aircrashes (17)

- AIRFLIGHT (1)

- airforce (2)

- AirIndia (1)

- airlines (10)

- AirlinesBudget (1)

- Airplane (21)

- AirplaneCrash (2)

- airpollution (9)

- Airport (1)

- airportinCambodia (1)

- Airports (8)

- Airportsecurity (1)

- Airtravel (19)

- Akihabara (1)

- AkindoSushiro (1)

- Albanese (1)

- alcohol (5)

- AlekMinassian (1)

- Aleppo (1)

- AlexanderDvornikov (1)

- Alibaba (1)

- alien (1)

- AlQaeda (1)

- Alzheimersdisease (2)

- Amadea (1)

- AmalClooney (1)

- Amazon (2)

- Amazon Deforestation (1)

- America (5)

- American politics (1)

- AmericanfootballNFL (1)

- Americanpolitics (9)

- ammo (1)

- ammunition (1)

- AMRO (1)

- ANA (1)

- AnatolyChubais (1)

- Anbinh (1)

- AnbinhPhan (1)

- ancienttomb (1)

- AndongBor (1)

- AndrewTate (1)

- AndyWarhol (1)

- AngelinaJolie (2)

- Angkor (1)

- Angkor Resources (1)

- AngkorAir (1)

- AngkorArchaeological (1)

- AngkorArchaeologicalPark (3)

- AngkorArcheological (2)

- AngkorArcheologicalPark (1)

- AngkorEnterprise (1)

- AngkorInternationalAirport (3)

- AngkorResources (2)

- AngkorWat (3)

- animals (31)

- animalwelfare (6)

- AnitaAlvarez (1)

- Anniversaries (3)

- Antarctica (3)

- Anthony (1)

- AnthonyAlbanese (1)

- antiaircraft (1)

- antiarmorsystems (1)

- antibodies (1)

- antidepressant (1)

- Antidumping (1)

- antigay (1)

- antitrust (2)

- antonyblinken (9)

- AnwarIbrahim (1)

- aodai (1)

- APEC (5)

- apology (6)

- apparel (1)

- Apple (9)

- Apps (1)

- APSARA (1)

- ApsaraNationalAuthority (2)

- ArchaeologyandAnthropology (3)

- archery (1)

- arctic (1)

- Ardern (1)

- Argentina (17)

- Armsandweapons (71)

- arrest (14)

- arrested (8)

- Arsenal (3)

- ArtandDesign (5)

- Artificial Intelligence (2)

- ArtificialIntelligence (2)

- artists (3)

- Arts (1)

- artwork (4)

- AsahiGroup (1)

- AsahiSuperDry (1)

- Ascend (1)

- Ascend Money (1)

- ASEAN (55)

- Asean chair (1)

- ASEAN China (1)

- ASEAN China summit (1)

- Asean envoy (1)

- Asean3 (1)

- ASEANSummit (1)

- AseanUSsummit (1)

- asia (1396)

- ASIA,Cambodia,National,Politics,Thailand,Cambodia,CMAA,landmine,Thailand (1)

- ASIA,Cambodia,National,Politics,Thailand,Cambodia,Thailand (1)

- ASIA,Cambodia,National,Thailand,Cambodia,Thailand,War (1)

- asian (1)

- Asian Development Bank (1)

- Asiana (2)

- AsianaAirlines (2)

- Asiancoconut (1)

- AsianDevelopmentBank (2)

- AsianGames (1)

- Asians (2)

- AsianTiger (1)

- AsiaPacific (4)

- AsiasTerritorialDisputes (3)

- assassination (1)

- assault (12)

- assetmanagement (2)

- Asteroids (2)

- AstraZeneca (1)

- Astrolab (1)

- Astronaut (2)

- astronomy (9)

- asylumseeker (2)

- Athletics (9)

- atomic (1)

- Attack (19)

- attacks (23)

- Attemptedmurder (1)

- Auctions (5)

- Audi (2)

- AudiR8 (1)

- AudiR8V10 (1)

- AudiSQ5 (1)

- AuditAuditors (1)

- Aung San Suu Kyi (7)

- AungSanSuuKyi (23)

- AunPornmoniroth (3)

- AustinLiJiaqi (1)

- Australia (103)

- Australiaelection (2)

- australian (1)

- AustraliaPM (1)

- Austria (2)

- AUTHORS (2)

- automation (1)

- automobileassemblyplant (1)

- Automobilesector (4)

- automotivetechnology (1)

- AutonomousPortinCambodia (2)

- Avangard (1)

- AVIATION (2)

- AviationAerospacesector (5)

- awards (1)

- Awards and prizes (1)

- Awardsandprizes (1)

- AwerMabil (1)

- AWSCambodia (1)

- AyatollahAliKhamenei (1)

- AyundaFazaMaudya (1)

- AZGroup (1)

- Azure (1)

- AzureOpenAI (1)

- babies (5)

- baby (5)

- babypowder (1)

- Badminton (1)

- Baghdad (1)

- Bahamas (2)

- Bahrain (1)

- Baidu (1)

- Bajarakitiyabha (1)

- Bajrakitiyabha (2)

- Bakong (6)

- Balakrishnan (1)

- Bali (6)

- BaliBombing (3)

- ballistic (4)

- ballisticmissile (7)

- BallondOr (1)

- BambooAirways (1)

- Banana (1)

- Bangkok (4)

- Bangkok Airways (1)

- BangkokAirways (1)

- BangkokFC (1)

- BangkokSiemReap (1)

- Bangladesh (18)

- Bank in Cambodia (3)

- BankCambodia (1)

- BankinCambodia (17)

- banking (3)

- BankingSector (1)

- banknotesofCambodia (1)

- BankofCambodia (1)

- BankofChinainCambodia (1)

- bankrobber (1)

- banks in Cambodia (1)

- BanksandFinancialInstitutions (4)

- Bans (4)

- Banteay Meanchey (1)

- BanteayMeanchey (9)

- BarackObama (2)

- barcelona (1)

- BarsandClubs (5)

- Baseball (1)

- BasketballPlayers (2)

- BassacRiver (1)

- BastilleDay (1)

- Battambang (20)

- BattambangAirport (1)

- battle (1)

- Bavarian (1)

- BavarianNordic (1)

- Bavet (4)

- Bavetexpressway (4)

- Bawagan (1)

- BBC (5)

- BBCdocumentary (1)

- beaten (1)

- Beauty (1)

- Beautypageants (3)

- BeeApp (1)

- BEER (2)

- BehaviourPsychology (2)

- Beijing (6)

- BeijingParalympics (1)

- BeijingWinterOlympics (1)

- belarus (3)

- belgium (3)

- BeltandRoad (1)

- BeltandRoadinitiative (2)

- Benedict (2)

- BenjaminFerencz (1)

- BenjaminNeta8203nyahu (1)

- berlin (1)

- BestExpress (1)

- BestHotelinCambodia (1)

- BestRiceAward2022 (1)

- BhumibolAdulyadej (1)

- bicycle (1)

- Biden (10)

- Bidengranddaughter (1)

- Big Data (1)

- BigBen (1)

- BigC (1)

- Bilateraltrade (1)

- Bill Clinton (1)

- BillBrowder (1)

- BillGates (3)

- billionaire (2)

- BillionairesMillionaires (8)

- Binance (2)

- Biodiversity (1)

- biofuel (1)

- BiomedicalsectorBiotechnology (1)

- BioNTech (9)

- biosecurity (1)

- biotech (2)

- BIOTECHNOLOGY (3)

- birds (3)

- Birkenstocks (1)

- birthday (2)

- birthrate (3)

- Bitcoin (4)

- bitcoins (1)

- blackout (1)

- BlackPanther (1)

- BlackSea (3)

- Blinken (3)

- blizzard (2)

- Blockchain (2)

- Blockchain negative reputation (1)

- BloodSlave (1)

- Bloomberg (1)

- Bloomberg forum (1)

- boat (12)

- BoatAccident (1)

- boatcapsizes (2)

- boatsinks (1)

- Bocugoz (1)

- Boeing (6)

- Boeing 737Max (1)

- Boeing737 (1)

- Boeing737800 (1)

- Boeing777 (1)

- Bokator (1)

- Bolivia (2)

- Bollywood (1)

- Bolsonaro (1)

- bomb (4)

- bomber (1)

- BombingsExplosions (24)

- BombThreat (1)

- Bombthreats (4)

- Bongbong (4)

- bonyfish (1)

- Books (6)

- Borey (1)

- BorisJohnson (17)

- BorisRomanchenko (1)

- boxing (1)

- BPC (1)

- Brain (2)

- brainshrinkage (1)

- braintumor (1)

- brand (4)

- Brazil (14)

- Brazilianfootball (1)

- breastmilk (1)

- Brexit (1)

- BRI (1)

- Bribery (5)

- BridgeCollapse (1)

- Britain (49)

- British (2)

- BritishElection2015 (1)

- BritishRoyalFamily (12)

- Britishroyalty (48)

- BrittneyGriner (1)

- BRONCHITIS (1)

- BTS (2)

- bubblegum (1)

- Bucha (2)

- BuckinghamPalace (1)

- buddhism (2)

- budget (1)

- budgettravel (1)

- BuenosAires (1)

- Buffalo (1)

- building (2)

- buildingcollapse (2)

- buildings (5)

- bullfighting (1)

- bunker (1)

- BurgerKing (1)

- bus (1)

- BusCrash (1)

- Business (504)

- Businessclosures (1)

- businessesinPhnomPenh (1)

- businessinCambodia (2)

- BYD (1)

- ByteDance (1)

- bZ4X (1)

- C02 (1)

- Cabinet (1)

- cafes (1)

- CafesandBakeries (1)

- CAIC (1)

- California (4)

- Californiastorm (1)

- Cambodia (610)

- Cambodia Agriculture (1)

- Cambodia agriculture sector (1)

- Cambodia Airline (1)

- Cambodia banana (1)

- Cambodia economic (2)

- Cambodia economy (1)

- Cambodia Pepper (1)

- Cambodia Realestate (1)

- Cambodia Rice (1)

- Cambodia Rice Federation (1)

- Cambodia tech entrepreneur (1)

- Cambodia Tech startup (1)

- Cambodia tech startups (1)

- Cambodia tyre factory (1)

- Cambodia young artist (1)

- cambodia-art-culture (2)

- cambodia-entertainment (154)

- cambodia-news (1379)

- cambodia-security (341)

- cambodia-sport (120)

- cambodia-traffic-accident (45)

- Cambodia’s Draft Law (1)

- Cambodia’s Draft Law on Investment (1)

- Cambodia’seconomic (1)

- Cambodia’seconomy (1)

- Cambodia2022economic (1)

- Cambodiaagricultural (1)

- CambodiaAirport (1)

- CambodiaAirportInvestment (1)

- CambodiaAirways (2)

- CambodiaAngkorAir (1)

- Cambodiabanana (3)

- Cambodiabanknotes (1)

- Cambodiabeer (1)

- Cambodiabeerbrewer (1)

- Cambodiabicycle (2)

- Cambodiablockchain (1)

- Cambodiacanfactory (1)

- Cambodiacapitalgainstax (1)

- Cambodiacashew (7)

- Cambodiacashewnut (1)

- CambodiaCashewnuts (2)

- Cambodiacashewproduction (1)

- CambodiaCasino (2)

- Cambodiacassava (2)

- CambodiaChamberofCommerce (1)

- CambodiaChina (1)

- CambodiaChinaFreeTrade (1)

- CambodiaChinaFreeTradeAgreement (1)

- Cambodiacrudeoil (1)

- Cambodiadigitalpayment (1)

- Cambodiadryrubber (2)

- Cambodiaecommerce (1)

- Cambodiaeconomic (4)

- Cambodiaeconomy (6)

- CambodiaElectricity (1)

- Cambodiaemarketplace (1)

- Cambodiaewallet (1)

- Cambodiaexport (5)

- CambodiaExpressway (1)

- CambodiaFDI (1)

- CambodiaFinancialTechnology (1)

- CambodiaFintech (2)

- Cambodiafragrantrice (1)

- CambodiaFreeTradeAgreement (1)

- CambodiaFruit (1)

- CambodiaGarment (1)

- CambodiaGarmentFootwear (1)

- Cambodiagasoline (1)

- CambodiaGDP (4)

- Cambodiaglutinousrice (1)

- CambodiaGold (2)

- Cambodiainflation (1)

- Cambodiainternet (1)

- Cambodiainternetsubscriber (1)

- CambodiaISP (1)

- CambodiaKorea (1)

- Cambodialandmine (1)

- CambodiaLongan (3)

- Cambodiamadeelectricmotorbike (1)

- CambodiaMango (1)

- CambodiamangoexportstoChina (1)

- CambodiaMobileOperator (1)

- Cambodiamobilepayment (1)

- Cambodianagriculturalproducts (1)

- CambodianBanana (4)

- CambodianBananaAssociation (1)

- Cambodiancorn (1)

- Cambodianeconomy (2)

- Cambodiangovernment (1)

- CambodiaNight (1)

- Cambodianlongan (1)

- Cambodianlongans (1)

- Cambodianmango (1)

- Cambodianmangoes (1)

- CambodianMicrofinanceAssociation (1)

- Cambodianmigrant (1)

- Cambodianmigrantworker (1)

- Cambodianongarment (1)

- Cambodianpepper (2)

- CambodianPrimeMinister (2)

- Cambodianproduct (2)

- Cambodianproducts (1)

- CambodianRestaurant (1)

- CambodianRice (4)

- Cambodianrubber (1)

- Cambodiaoil (2)

- CambodiaPepper (2)

- CambodiaPrimeMinister (1)

- CambodiaRailwayStation (1)

- CambodiaRealestate (1)

- CambodiaRice (20)

- cambodiariceexport (3)

- CambodiaRiceFederation (2)

- CambodiaRoyalRailway (1)

- Cambodiarubber (5)

- Cambodiarubberexport (1)

- CambodiaRussia (1)

- CambodiaSecuritiesExchange (2)

- Cambodiaswiftlet (1)

- CambodiaTax (4)

- CambodiaTechExpo2022 (1)

- CambodiaTycoon (1)

- Cambodiatyrefactory (1)

- Camel (1)

- Camera (1)

- CamGSM (1)

- Camlife (1)

- Canada (17)

- Canadia Bank (1)

- CanadiaBank (1)

- cancer (9)

- Cancerdiagnosis (1)

- Candidates (4)

- Candlelight (1)

- CandlelightParty (1)

- Candy (1)

- Canfactory (1)

- cannabis (11)

- Cannabiscafe (1)

- CannesFilmFestival (1)

- capitalgainstax (1)

- car (7)

- Carbonmonoxide (1)

- Careers (1)

- CargoShip (2)

- CarReview (13)

- Cars (11)

- Cartel (1)

- Cashew (4)

- Cashewgrowers (1)

- Cashewnut (3)

- CashewNutAssociationofCambodia (1)

- Cashewnuts (2)

- cashewprocessingfactory (1)

- cashewproducer (1)

- cashewproduction (1)

- cashless (1)

- casino (1)

- CasinoinCambodia (4)

- casinooperator (1)

- casinos (3)

- Cassava (2)

- cassavaprice (2)

- castration (1)

- CathayPacific (3)

- CathedraleNotreDamedeparis (1)

- CatherinePrincessofWales (1)

- CatholicChurch (6)

- Cats (2)

- CausinghurtGrievoushurt (1)

- CBC (1)

- CCC (1)

- CCFTA (1)

- CDC (4)

- ceasefire (1)

- celand (1)

- celebrities (4)

- celebrity (2)

- Celimo Tires (1)

- Cellcard (3)

- Censorship (2)

- CentersforDiseaseControlandPrevention (1)

- CentralAmerica (1)

- CentralBanks (1)

- CentralIntelligenceAgency (1)

- CEOS (1)

- CES (1)

- CGMC (1)

- Chamberlain (1)

- championbelt (1)

- ChampionsLeague (5)

- Channel (1)

- Chanthaburi (1)

- Chanthol (2)

- Charity (3)

- chatbot (1)

- ChatGPT (2)

- Chea Kok Hong (1)

- Chea Serey (3)

- Chea Vandeth (1)

- CheaChanto (1)

- CheaSerey (4)

- cheating (2)

- cheetah (1)

- chelsea (6)

- chemicalattack (1)

- chemicalcastration (1)

- Chernobyl (1)

- CheslieKryst (1)

- chess (2)

- Chestertons (1)

- chicken (2)

- Chief Bank (1)

- ChiefBank (1)

- child (2)

- childabuse (1)

- childcare (1)

- Childnutrition (1)

- childrearing (1)

- children (29)

- ChildrenandYouth (19)

- Chile (2)

- China (321)

- China ASEAN (2)

- china63391 (1)

- ChinaCambodiaTradeandInvestment (1)

- chinacrime (1)

- ChinaEastern (1)

- Chinaeconomy (1)

- Chinaflight (2)

- ChinainvadesTaiwan (1)

- Chinalocksdown (1)

- chinamilitary (4)

- Chinapolitics (3)

- ChinaTaiwan (1)

- Chineseastronaut (1)

- Chinesebusinessman (1)

- Chineseeconomy (1)

- Chineseinvestment (1)

- ChineseNewYear (4)

- Chinesespacestation (1)

- Chinesetourists (2)

- chipmaking (1)

- ChipWar (1)

- Chlorineleak (1)

- ChrisHipkins (1)

- ChrisJohnson (1)

- Christianity (1)

- Christmas (3)

- Christmas 2021 (1)

- Chun Dooh wan (1)

- Churches (8)

- CIA (1)

- CinemaWorld (1)

- Citizenships (4)

- Civil War (1)

- Civillawsuits (2)

- civilrights (3)

- CivilWar (1)

- Clans (1)

- CleanEnergy (1)

- Clearview (1)

- ClearviewAI (1)

- climate (3)

- Climate Change (1)

- ClimateChange (68)

- Climbing (4)

- ClinicalResearch (1)

- Cloning (1)

- clothes (2)

- CloudCambodia (1)

- Cloudservice (1)

- CNN (1)

- CNRP (1)

- coachella (1)

- Coca (1)

- Cocachewing (1)

- CocaCola (2)

- CocaColaCambodia (1)

- Coconut (2)

- coffee (1)

- Coin (1)

- Coinbase (1)

- CoinDesk (2)

- ColdWar (3)

- CollectorsCollections (1)

- colombia (3)

- Colonialism (2)

- comics (2)

- commercial bank in Cambodia (1)

- commercialbankinCambodia (8)

- Commonwealthcountries (1)

- Communism (3)

- CommunistParty (6)

- Communitycentresandclubs (1)

- Competition (4)

- Computercrimes (1)

- Computers (1)

- concerts (3)

- concertstampede (1)

- conflictinUkraine (2)

- Congo (1)

- ConservationPreservation (4)

- construction (3)

- constructionsector (1)

- consumerproducts (1)

- Contamination (1)

- Contests (1)

- Coogler (1)

- Cooking (2)

- cookingoil (2)

- cookingoilprice (1)

- Cooper (1)

- COP27 (7)

- copper (1)

- coppergold (1)

- CopyrightIntellectualproperty (2)

- corgis (2)

- CorollaCross (1)

- corona virus (3)

- coronation (2)

- coronationceremony (1)

- coronavirus (324)

- coronavirus67923 (1)

- Coronavirusclinicaltrials (1)

- coronavirusdisease2019 (3)

- Corruption (15)

- cosmeticsfactory (1)

- costarica (3)

- CostcuttingRestructuring (2)

- costmanagement (1)

- Costofliving (4)

- coughsyrup (2)

- Council of the Development of Cambodia (1)

- counter terrorism (1)

- CounterfeitsForgery (2)

- Countervailing (1)

- Coup (11)

- CourtofAppeal (1)

- Covax (1)

- COVIC19 (1)

- Covid (12)

- COVID 19 (2)

- COVID-19 (5)

- Covid-19 variant (1)

- COVID19 (335)

- COVID19 lockdown (1)

- Covid19 Testing (4)

- Covid19Omicronvariant (59)

- Covid19oral (1)

- Covid19outbreak (1)

- Covid19pandemic (4)

- Covid19pill (1)

- Covid19quarantine (1)

- Covid19Testing (6)

- COVID19Therapies (2)

- Covid19vaccinations (11)

- COVID19vaccine (4)

- COVIDsymptoms (1)

- Covidvaccine (2)

- Covifenz (1)

- CPBank (1)

- CPCambodia (2)

- crackdown (1)

- crash (5)

- CRBC (1)

- Credit Bureau Cambodia (1)

- Credit Guarantee Corporation of Cambodia (1)

- Cricket (2)

- crime (65)

- Crimea (1)

- Crimescene (2)

- criminalhideout (1)

- Criminalinvestigations (6)

- CristianoRonaldo (13)

- CristinaBawagan (1)

- croatia (4)

- Crocodile (3)

- cross border travel (1)

- crossborder travel (3)

- crossborderdelivery (1)

- crossbordertravel (8)

- CrowdfundingandFundraising (2)

- CrownPrince (1)

- crudeoil (3)

- Cruise (3)

- cruises (2)

- crypto (4)

- cryptoamulet (1)

- Cryptocurrency (15)

- cryptocurrencyfraud (1)

- cryptocurrencyrisks (1)

- cryptoprojectinCambodia (1)

- CrystalPalace (1)

- CSX (6)

- CSXTrade (1)

- Cuba (5)

- cuisine (3)

- culture (8)

- currencies (3)

- Customerservice (2)

- cyberattack (8)

- Cybercrime (1)

- cyberscammer (1)

- cybersecurity (18)

- cyberwarfare (2)

- cyclo (1)

- Cyclones (10)

- Daiso (1)

- damage (2)

- daminCambodia (1)

- DanuphaKhanatheerakul (1)

- Dara Sako rInternational Airport (1)

- Dara Sakor (1)

- DaraSakor (3)

- DaraSakorInternationalAirport (2)

- DaraSakorproject (1)

- DariaDugina (1)

- data (6)

- Dataanalyticsscience (1)

- dataleak (7)

- datamanagement (1)

- Dataprivacysecurity (12)

- datasecurity (1)

- DatingRelationships (3)

- daughter (4)

- dead (7)

- dearMoon (1)

- death (97)

- DeathPenaltyCapitalPunishment (8)

- deaths (120)

- deathsentence (1)

- debt (3)

- DebtTrap (1)

- deepfake (2)

- deepseaport (1)

- Defamation (5)

- defence (9)

- Defence and military (1)

- Defenceandmilitary (136)

- defencezone (2)

- defenseexercise (1)

- defraudingcustomer (1)

- delay (1)

- Deliveroo (1)

- Delta (2)

- Delta variant (1)

- Deltacron (1)

- Deltavariant (3)

- Dementia (2)

- democracy (9)

- DemocraticPresidentJoeBiden (1)

- DemocraticProgressiveParty (1)

- DemocraticRepublicoftheCongo (1)

- denmark (3)

- DennisRodman (1)

- dessert (1)

- DestinAsian (1)

- developmentinCambodia (1)

- diabetes (1)

- diagnosistreatment (1)

- Diana (4)

- Diaper (1)

- dictator (1)

- DieAnotherDay (1)

- DiegoMaradona (1)

- DieselPetrol (1)

- diet (1)

- Digital (8)

- digital payment (1)

- digital platform for Cambodia (1)

- digital tax (1)

- DigitalCurrency (2)

- digitaldollar (1)

- digitaleconomy (2)

- Digitalisation (1)

- digitalisationinCambodia (1)

- digitalpayment (2)

- DigitalpaymentinCambodia (1)

- DigitalTransformation (2)

- DineAway (1)

- Dinosaur (2)

- Diplomats (8)

- direct flight to Cambodia (1)

- direct flights to Cambodia (1)

- director (1)

- disabilities (2)

- Discrimination (5)

- Diseases (15)

- Disorderlybehaviour (1)

- DithTina (2)

- Divinecrocodile (1)

- Divorces (2)

- DJI (2)

- DmitryMedvedev (1)

- doctor (1)

- DoctorsSurgeons (1)

- Documentaries (2)

- dogbreed (2)

- Dogecoin (1)

- DogLover (1)

- Dogs (3)

- dolphin (2)

- DomesticViolence (2)

- DominoPizza (1)

- Donald Trump (1)

- DonaldTrump (42)

- donations (4)

- DonQuijote (1)

- Douyin (1)

- drinking (2)

- Drivingsimulator (1)

- drone (7)

- Drones (17)

- Drought (2)

- Droughts (3)

- Drownings (4)

- drug (11)

- drugoffences (5)

- Drugs (20)

- dryrubber (1)

- Dubai (4)

- Dubaicamel (1)

- durian (2)

- duriangrower (2)

- durians (2)

- duriansfromChanthaburi (1)

- Duterte (3)

- Dvornikov (1)

- Dwarfelephant (1)

- Earth One (1)

- EarthOne (20)

- earthquake (1)

- Earthquakes (27)

- EastAntarctica (1)

- EastAsianSummit (1)

- EastTimor (1)

- EBA (1)

- Ebola (2)

- Ebolaoutbreak (1)

- EckardMickish (1)

- ecommerce (3)

- ecommerceVAT (1)

- economic (1)

- economic growth forecast (1)

- economiccensus (2)

- economiccrisis (7)

- EconomicGrowth (2)

- EconomicSlowdown (1)

- EconomicZone (1)

- Economy (57)

- Ecuador (2)

- EDC (1)

- Education (3)

- EducationandSchools (5)

- eggs (2)

- eggtart (1)

- Egypt (7)

- EgyptAirflightMS804 (1)

- EgyptAirplanecrash (1)

- EiffelTower (2)

- elderly (3)

- elearning (1)

- electedpresident (12)

- ELECTIONS (68)

- electoral fraud (1)

- Electricandhybridvehicles (4)

- electriccars (7)

- ElectricityandPower (17)

- electricitytariff (1)

- electricmotorbike (1)

- electricmotorcyclesinCambodia (1)

- electricvehicle (1)

- electricvehicles (6)

- Electronics (2)

- elephant (1)

- Elizabeth (8)

- Elon Musk (1)

- ElonMusk (42)

- EMAutomobile (1)

- Embargoesandeconomicsanctions (19)

- Emergencies (9)

- EmeritusBenedict (1)

- EmmaChamberlain (1)

- EmmanuelMacron (7)

- eMoney (1)

- eMoneyPayment (1)

- EmperorNaruhito (1)

- EmployersEmployees (7)

- EmploymentUnemployment (9)

- endangeredspecies (1)

- Endangeredthreatenedspecies (2)

- energy (12)

- Energycrisis (1)

- EngineersEngineering (1)

- Englandfootballteam (2)

- EnglishLanguage (2)

- Entertainment (142)

- Entrepreneur (2)

- EntrepreneursAssociationofCambodia (1)

- Environment (3)

- ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES (1)

- ENVIRONMENTALISSUES (36)

- EPLEnglishPremierLeague (10)

- Equinox (2)

- EquinoxatAngkorWat (1)

- ErikCarnell (1)

- ErikTenHag (1)

- Ernie (1)

- ESA (1)

- ESchoolCambodia (1)

- escooter (1)

- eSportinCambodia (1)

- Estonia (1)

- Ethereum (1)

- ethiopia (1)

- EU (8)

- EUEuropeanUnion (31)

- EUROCHAM (1)

- Europe (18)

- European Union (1)

- EuropeanUnion (10)

- Eva Premium Ice (1)

- EVCar (1)

- EVcharging (1)

- EVchargingstation (1)

- evehicle (1)

- evehicles (2)

- Events (4)

- Evergreen (1)

- evicted (1)

- ewallet (1)

- exhibition (1)

- exile (1)

- explosion (5)

- export (10)

- exportsfromCambodia (1)

- Express way in Cambodia (1)

- expressway (5)

- expresswayofCambodia (1)

- ExtortionBlackmail (1)

- EZECOM (5)

- face masks (1)

- Facebook (19)

- Facebookfounder (1)

- facemasks (6)

- facialrecognition (1)

- Factories (1)

- factoriesinPhnomPenh (1)

- factoryinCambodia (1)

- factoryinSihanoukville (1)

- FACup (1)

- Fagradalsfjall (1)

- fake (1)

- fakenews (4)

- FakePutin (1)

- Fakereview (1)

- falseadvertising (1)

- Families (2)

- Family (7)

- Family feuds (1)

- Familybusinesses (1)

- Familyfeuds (1)

- FarmersinCambodia (1)

- Fashion (8)

- FashionDesigners (1)

- Fashionmodels (1)

- Fashionshows (1)

- fastfood (3)

- fatality (1)

- fattykatsuo (1)

- FB (5)

- FBI (3)

- fda (3)

- FDI (2)

- features (77)

- Ferdinand Marcos (1)

- FerdinandMarcos (5)

- Ferrari (1)

- FerrariF1 (1)

- ferry (3)

- ferry accident (1)

- ferryaccident (1)

- ferryfire (1)

- FestivalsCelebrations (9)

- feversyrup (1)

- fiberopticcable (1)

- Fibre2Fashion (1)

- FIFA (40)

- fight (7)

- fighterjet (1)

- fighterjets (6)

- fiji (1)

- Filipino protester (1)

- film (2)

- finance (3)

- financial inclusion in Cambodia (1)

- Financialaid (1)

- Financialcrimes (2)

- Financialcrisis (8)

- FinancialManagementInformationSystem (1)

- financing (1)

- fine (3)

- finland (7)

- FinlandPM (1)

- Fintech (1)

- Fintech hub in Cambodia (1)

- Fire (3)

- firefighter (7)

- fires (21)

- Firesafetyrules (1)

- fireworks (1)

- Fisheriessector (2)

- flight5735 (1)

- flights to Cambodia (1)

- flightsimulator (1)

- flightsimulatorinCambodia (1)

- FlightstoSiemReap (1)

- floatingcity (1)

- FloatingRestaurant (1)

- flood (4)

- Flooding (23)

- Floods (32)

- Florida (1)

- Fluvaccines (1)

- flyingcar (1)

- FMIS (1)

- Food (32)

- food court in Cambodia (1)

- FoodandBeveragesector (2)

- foodanddrink (1)

- FoodandDrinks (11)

- foodcrisis (1)

- FoodDelivery (2)

- fooddeliverycompanyinCambodia (1)

- Fooddeliveryservices (1)

- Foodexport (1)

- Foodhygienesafety (2)

- foodinCambodia (1)

- Foodpanda (1)

- foodprices (6)

- foods (14)

- Foodsafety (2)

- Foodsecurity (2)

- Foodshortage (1)

- foodsupplies (1)

- Foodtrends (1)

- FootandMouthDisease (1)

- football (104)

- Footballmatches (6)

- Footballplayers (21)

- footballstampede (1)

- footwear (3)

- Ford (1)

- FordMotorCompany (1)

- Fordvehicleassembly (1)

- foreign (6)

- ForeignDirectInvestmentinCambodia (1)

- foreigner (3)

- ForeignExchange (2)

- foreignpolicy (3)

- ForeignWorkers (3)

- forest (3)

- forestfires (4)

- Formula1 (1)

- FormulaOne (1)

- fortnite (1)

- fortunetelling (1)

- Fossilfuels (8)

- Foxconn (3)

- foxnews (1)

- FPDA (1)

- FRANCE (47)

- Franceelection (2)

- Fraud (8)

- freespeech (4)

- freetradeagreement (3)

- French (1)

- Frenchpresidentialelection2017 (1)

- FrenchSpiderman (1)

- freshCambodiabanana (1)

- freshmango (3)

- friedchicken (1)

- Friendship (1)

- fruit (6)

- FTB (1)

- FTBBank (3)

- FTBMobile (1)

- FTBTower (1)

- Fukuoka (1)

- Fukushima (5)

- fully vaccinated (1)

- Fumio (1)

- FumioKishida (30)

- FUNANMicrofinance (1)

- Fund (5)

- Funeral (19)

- G20 (12)

- G20Groupof20 (7)

- G20meeting (1)

- G20summit (16)

- G7 (3)

- G7Groupof7 (15)

- G7summit (1)

- galaxy (5)

- Gambia (2)

- Gambling (9)

- gamblinglaw (1)

- game (5)

- Gaming (1)

- GamingVideogames (3)

- Gandhis (1)

- Gangnam (1)

- Gangs (6)

- GardenResidencycondominium (1)

- garment (1)

- garment industry in Cambodia (1)

- garment manufacturers in Cambodia (1)

- Gas (2)

- gasoline (1)

- gasolinepoweredcar (1)

- gasolineprice (2)

- gasprices (3)

- gay (1)

- gaylaw (1)

- gaymen (1)

- gaynightclub (1)

- gaysex (2)

- Gazprom (1)

- GCLifeInsurance (1)

- GDP (5)

- GDT (4)

- Genderequality (1)

- genderinequality (3)

- Genderissues (1)

- General Department of Taxation (1)

- general-knowledge (9)

- GeneralDepartmentforTaxation (1)

- GeneralDepartmentofTaxation (5)

- GeneralTyreTechnology (1)

- Genocide (4)

- GenocideCrimesagainsthumanity (14)

- genocideinUkraine (1)

- Genting (1)

- geopolitics (14)

- GeorgeBush (1)

- GeorgeW.Bush (1)

- GeorginaBeyer (1)

- German (1)

- GERMANY (43)

- GFTgoods (1)

- Ghana (1)

- GhibliGT (1)

- GhibliGTHybrid (1)

- Ghost (1)

- Ghostdrone (1)

- Ghostdrones (1)

- Ghostwriter (1)

- Giantrat (1)

- Giantstrawberry (1)

- giantsunfish (1)

- globaleconomic (1)

- globalfoodsupply (1)

- globaloilmarket (1)

- globalsupplychain (1)

- globalwarming (19)

- glovemanufacturing (1)

- Gojek (1)

- gold (2)

- gold mine (1)

- GoldenTriangle (1)

- goldextraction (1)

- goldfish (1)

- goldmine (1)

- goldmineinIndonesia (1)

- Golf (1)

- GoodFriday (1)

- Google (3)

- Gorbachev (2)

- GordonMoore (1)

- Gossan Hills prospects in Cambodia (1)

- GossanHills (1)

- GotabayaRajapaksa (1)

- GoTo (1)

- GovernmentBorrowingDebt (2)

- GPT4 (1)

- Grab (2)

- Graft (2)

- Graham (1)

- GrandCathayInvestmentTrust (1)

- GrandDiamondCitycasino (1)

- Graphicnovels (1)

- GREECE (2)

- Greenland (1)

- GreenSustainableVentures (1)

- GTD (1)

- GTSEZ (1)

- Guangxi (1)

- Guangzhou (1)

- Guatemala (1)

- Gucci (1)

- Guinness (1)

- GuinnessWorldRecord (1)

- GuinnessWorldRecords (1)

- Guncrime (2)

- gunfree (1)

- gunlaws (1)

- GuoWengui (1)

- gymnastics (1)

- Hacker (8)

- Hacking (6)

- Hairdresser (2)

- Halloween (20)

- Halloweencrush (1)

- Halloweendisaster (1)

- Halloweenstampede (3)

- HamidSafi (1)

- handgun (1)

- HandofGod (1)

- Harassment (1)

- HariRayaPuasa (2)

- HarryMaguire (1)

- Hatecrime (1)

- Hatespeech (1)

- HatthaBank (2)

- HAVANA (1)

- Hawaii (1)

- Health (198)

- Health and Well being (1)

- Health care Professionals (2)

- HealthandWellbeing (15)

- Healthcare (5)

- HealthcareProfessionals (2)

- HeartCardiacdiseases (2)

- heatwave (17)

- helicopter (2)

- HelicopterCrash (1)

- HengSamrin (1)

- HenryKissinger (1)

- HepatitisA (1)

- hepatitisE (1)

- heritage (4)

- HerryWirawan (1)

- HFMDHand (1)

- hijab (1)

- hikikomori (1)

- Hillary Clinton (1)

- Himalayan (3)

- HIMARS (2)

- Hindu (2)

- Hinduism (3)

- Hinnamnor (1)

- Hipkins (1)

- HirokazuMatsuno (1)

- history (12)

- HM (2)

- HoChiMinhCity (1)

- hockey (1)

- Hollywood (1)

- Holocaust (1)

- Home (2)

- homebasedlearning (1)

- homeless (4)

- homesales (1)

- Homicide (1)

- Homosexuality (1)

- HomosexualityLGBT (23)

- Honda2023 (1)

- HondaFreed (1)

- Honduras (1)

- Hong Lai Huat (2)

- HongKong (25)

- HongKongiconic (1)

- HongKongsiconicJumboFloatingRestaurant (1)

- horseradish (1)

- hospital (10)

- Hospitals (3)

- hostage (4)

- hotelinHongKong (1)

- Hotels (2)

- HouseSpeaker (1)

- housingcrisis (1)

- howtousegun (1)

- HRAsia (1)

- HSBC (1)

- HSPGC (1)

- Huadian (1)

- Huawei (1)

- human immune system (1)

- human rights (2)

- HumanDNA (1)

- humanimmunesystem (2)

- HumanitarianaidDisasterrelief (8)

- Humanitarianorganisations (1)

- humanrights (41)

- humantrafficking (2)

- Hun Manet (1)

- Hun Sen (18)

- HunKosal (1)

- HunSen (89)

- Hwasong (3)

- Hwasong17 (1)

- Hyatt (1)

- Hyatt Regency (1)

- HyattRegencyPhnomPenh (1)

- hydropower (1)

- hypersonic (2)

- hypersonicmissile (2)

- hypersonicmissiles (2)

- hypersonics (1)

- Hyundai (1)

- ICBM (10)

- ICBMtest (1)

- ICC (1)

- illegal (4)

- Illegalbetting (3)

- illegalgamblin (1)

- Illegallogger (1)

- illness (1)

- Illnesses (1)

- image (2)

- IMFInternationalMonetaryFund (3)

- immigration (1)

- Imperial family (1)

- impunity (1)

- ImranKhan (6)

- Imvanex (1)

- Incomeinequality (1)

- independence (1)

- india (130)

- Indiamadesyrup (1)

- Indianraildisaster (1)

- Indiantravellers (2)

- Indonesia (157)

- Indonesiafootball (1)

- Indonesianpolitics (4)

- IndonesianPresident (1)

- IndoPacific (4)

- IndustrialRelations (1)

- infectious disease (1)

- Infectious diseases (1)

- infectiousdisease (12)

- Infectiousdiseases (9)

- Inflation (12)

- inflationinCambodia (2)

- InflationPriceLevel (25)

- Influencer (1)

- Influenza (1)

- informationsecurity (2)

- infrastructure (2)

- infrastructureinCambodia (1)

- Injured (4)

- innovation (2)

- Insects (1)

- Instagram (7)

- Instagraminfluencer (1)

- insulting (2)

- insultingmonarchy (1)

- Insurance (1)

- Intel (1)

- international-news (213)

- InternationalAirport (1)

- InternationalAtomicEnergyAgency (1)

- InternationalCriminalCourt (4)

- internationaldeepseaport (1)

- Internationallaw (2)

- InternationalOlympicCommittee (2)

- internationalpayments (1)

- InternationalSpaceStation (3)

- InternationalTrade (1)

- Internet (1)

- Internetcrimesandscams (6)

- internetusersinCambodia (1)

- InterPride (1)

- investinCambodia (1)

- investing (1)

- Investment (11)

- investment projects in Cambodia (1)

- investmentinCambodia (2)

- investmentprojectinCambodia (1)

- investments (1)

- Investors (5)

- IOC (1)

- iPhone (3)

- Iran (23)

- irannucleardeal (1)

- Iraq (7)

- Ireland (2)

- Irishprimeminister (1)

- IsabellePlumereau (1)

- ISI (1)

- ISIS (3)

- Islam (3)

- Islamic (1)

- isolationshelters (1)

- ISPinCambodia (1)

- Israel (19)

- Israeli (2)

- Istanbul (3)

- ISUZU (1)

- ISUZUCambodia (1)

- Itaewon (17)

- Italy (16)

- IterPlus (1)

- Ivermectin (2)

- Jacinda (1)

- JacindaArdern (2)

- JackMa (1)

- Jaguar (1)

- Jail term (1)

- Jailterm (10)

- JairBolsonaro (1)

- jakarta (7)

- Jakartaattacks (1)

- JAL (1)

- Jamaica (1)

- Japan (218)

- Japanese (5)

- Japanese investment projects in Cambodia (1)

- JapaneseEmperor (1)

- japanesefood (1)

- JapanPM (1)

- Java (1)

- Javelin (1)

- Javelinmissile (1)

- Javelins (1)

- JeffBezos (4)

- JemaahIslamiah (1)

- JeremyLin (1)

- Jerusalem (5)

- Jerusalemholysite (1)

- JETRO (2)

- JETROCambodia (1)

- jets (4)

- JetserviceinCambodia (1)

- Jetstar (2)

- JetstarAirways (1)

- Jewellery Gemstones (1)

- JewelleryGemstones (1)

- Jews (2)

- Jiang (1)

- JiangZemin (1)

- JillBiden (1)

- Jinping (1)

- Jobcuts (4)

- jobs (8)

- Joe Biden (3)

- JoeBiden (83)

- JohnsonJohnson (1)

- Jokowi (2)

- JokoWidodo (14)

- JoshHawley (1)

- Joshimath (1)

- Journalism (10)

- journalist (1)

- JSLand (1)

- Jubilee (2)

- JumboFloatingRestaurant (1)

- Junta (2)

- JustinTrudeau (1)

- KalaniDavid (1)

- Kaliningrad (1)

- Kamala Harris (1)

- KamalaHarris (1)

- kamikaze (1)

- Kampong Cham (1)

- Kampong Speu (3)

- KampongCham (9)

- KampongChhnang (6)

- KampongSpeu (13)

- KampongSpeuPalmSugar (1)

- KampongThom (11)

- Kampot (33)

- Kampot pepper (1)

- KampotLogistics (1)

- Kampotmultipurposeport (1)

- Kampotpepper (2)

- Kampotport (1)

- Kandal (31)

- KaneTanaka (1)

- kangaroo (1)

- Kangarooattack (1)

- KaoKimHourn (1)

- KarineJeanPierre (1)

- KateMiddleton (3)

- KATHMANDU (1)

- katsuo (1)

- Kazakhstan (2)

- Kei Komuro (1)

- KeiKomuro (1)

- KemSokha (1)

- KennethTsang (1)

- Kenya (1)

- Kep (13)

- keystonexl (1)

- KGMobility (1)

- KhairussalehRamli (1)

- Khamenei (1)

- Khaosoi (1)

- KhmerEnterprise (1)

- Khmermartialarts (1)

- KHQR (2)

- KIAMotors (1)

- kickboxer (1)

- KidnapAbduction (4)

- kidney (1)

- Kilimanjaro (1)

- Kim Jong Un (2)

- KimIlSung (1)

- KimJongil (1)

- KimJongUn (45)

- kindness (2)

- kingcharles (16)

- KingCharlesIII (13)

- KingMahaVajiralongkorn (2)

- Kishida (10)

- Kissinger (1)

- KithMeng (7)

- KitKat (1)

- KiwiMart (1)

- Kiyomizutemple (1)

- KK (1)

- KnightFrank (1)

- Koh Kong (5)

- KohKhaiHuaRoh (1)

- KohKong (14)

- KohRong (1)

- KohRongisland (1)

- KohSramoch (1)

- KohTonsay (1)

- KOI (1)

- KOI Thé (1)

- KOI Thé Cambodia (1)

- Koi Thé Reach Theany (1)

- KokoCici (1)

- Komodo (1)

- Komododragons (1)

- Kong Vibol (1)

- KongVibol (2)

- KonstantinMalofeyev (1)

- Kopiko (1)

- Kopikocandy (1)

- Korea (1)

- KoreaFreeTradeAgreement (1)

- KoreanAir (3)

- Koreanfood (1)

- KoSamui (1)

- Kouch Chamroeun (1)

- KouchChamroeun (1)

- kpop (3)

- Kratie (2)

- Kremlin (1)

- KrisEnergy (3)

- KrishnakumarKunnath (1)

- KunBokator (1)

- Kunming (1)

- KunNhem (1)

- KunNhim (1)

- Kunthea (1)

- Kyiv (12)

- KylianMbappe (1)

- Kyoto (1)

- KySereyvath (2)

- Labourissues (9)

- labourpolicy (1)

- Labourshortage (1)

- LakeVictoria (1)

- LaLiga (1)

- Landdegradation (1)

- LandRover (1)

- landslide (4)

- Lanmei (2)

- Lanmei Airlines (1)

- LanmeiAirlines (1)

- Laos (4)

- lasvegas (2)

- Latvia (2)

- law (12)

- Law on Investment (1)

- Law suits (1)

- Lawandlegislation (35)

- Lawenforcement (3)

- lawinCambodia (1)

- lawontaxation (1)

- Lawsuits (36)

- lawyers (3)

- LDC (1)

- Leaders (6)

- leak (5)

- leastdevelopedcountry (1)

- LeeHsienLoong (4)

- LeeJihan (1)

- LeeKuanYew (2)

- LeeMyungbak (1)

- lego (1)

- lendweaponstoUkraine (1)

- LeniRobredo (1)

- LeRoyal (1)

- Lesbian (1)

- LETTER (1)

- LewisHamilton (1)

- LGBT (20)

- LGBTQ (5)

- libel (1)

- Libya (1)

- licenceplate (1)

- Life style (5)

- Lifeexpectancy (1)

- Lifehacks (1)

- Lifestyle (270)

- LiJiaqi (1)

- Limaairport (1)

- LimChhivHo (1)

- LindseyGraham (1)

- LiNing (1)

- Lion (1)

- LionelMessi (16)

- Lithuania (3)

- liverdisease (1)

- liverpool (7)

- LiverpoolClub (1)

- livestockdiseases (1)

- livestream (2)

- livingcost (1)

- LizTruss (1)

- LloydAustin (2)

- loansharks (1)

- lockdown (16)

- logistics (1)

- LONDON (11)

- Longan (2)

- longanfarm (1)

- longanfruit (1)

- LosAngeles (1)

- lost (1)

- Lottery (3)

- love (2)

- lowbirthrates (1)

- lowcostsoba (1)

- Lowwageworkers (2)

- LunarNewYear (2)

- LunBorey (1)

- luxury (2)

- luxurybrands (2)

- LVMH (1)

- M1Abrams (1)

- Macau (1)

- MacroeconomicResearchOffice (1)

- Maezawa (2)

- mafia (1)

- Magawa (1)

- magazine (1)

- MagnitskyAct (1)

- MaharajaofIndia (1)

- MahaVajiralongkorn (1)

- makeover (1)

- Mako (1)

- Mako Komuro (1)

- MakotoOniki (1)

- Makro (2)

- MakroCambodia (1)

- Malaysia (40)

- Malaysia Airlines (1)

- MalaysiaAirlines (3)

- MalaysiaAirlinesFlight370 (1)

- Malaysian flights to Cambodia (1)

- Malaysianbusinesspeople (1)

- Malaysiandurian (1)

- Malaysianeconomy (1)

- Malaysianroyalty (1)

- Maldives (2)

- Malls (1)

- Malofeyev (1)

- malware (1)

- ManchesterCity (8)

- ManchesterUnited (16)

- Mango (4)

- mangoesfromCambodia (2)

- mangoproduction (1)

- Manny Pacquiao (1)

- MannyPacquiao (2)

- Manufacturers (2)

- manufacturers in Cambodia (1)

- manufacturing (5)

- Maradona (2)

- Marcos (4)

- marijuana (3)

- MarilynMonroe (1)

- MarineLePen (2)

- marinelife (4)

- marinemonster (1)

- maritimeaffairs (5)

- MaritimeandShipping (6)

- Mariupol (1)

- MarketinCambodia (1)

- marketShare (2)

- MarkZuckerberg (3)

- marriage (7)

- Märtha (1)

- MärthaLouise (1)

- martialarts (1)

- MartinBroughton (1)

- Maserati (1)

- MaseratiGhibliGTHybrid (1)

- massacre (1)

- massivecarp (1)

- masskilling (1)

- massmurderer (1)

- MassShooting (3)

- Mastercard (1)

- MattiaBinotto (1)

- MaudyAyunda (1)

- Maybank (1)

- Mayday (1)

- mayor (2)

- Mayura (1)

- MB Bank (1)

- Mbappe (2)

- MBBank (2)

- MBBankCambodia (1)

- McDonald (2)

- McDonalds (7)

- MEDIA (9)

- Medical (6)

- Medical research (1)

- medicalcannabis (1)

- medicalcases (2)

- medicalmarijuana (1)

- Medicalresearch (6)

- medicaltreatment (2)

- medicine (15)

- medicineshortage (1)

- MeditationMindfulness (1)

- Medtecs (1)

- meghanduchessofsussex (2)

- MeghanMarkle (4)

- Megi (1)

- MekongRiver (1)

- Melbourne (1)

- MembersofParliament (3)

- Memoirs (1)

- memoryloss (1)

- Mengly (1)

- MenglyJ.Quach (1)

- mentalhealth (5)

- mentallydisabled (1)

- Messaging (2)

- Messi (8)

- Meta (7)

- metals (1)

- MetaPlatforms (2)

- Meteor (1)

- Meteorologist (1)

- Meteorology (2)

- Metfone (2)

- Metformin (1)

- Methamphetamine (1)

- mexico (13)

- MG (1)

- MGHS (1)

- MGHSExclusive (1)

- MH17 (4)

- MH17crash (2)

- MH17investigation (1)

- MH17investigations (1)

- MH370 (1)

- MichaelBloomberg (1)

- MichaelJordan (1)

- MicheálMartin (1)

- Michigan (1)

- Mickish (1)

- Microsoft (2)

- MiddleEast (3)

- migrant (6)

- MigrantsMigrationlegal (2)

- MikePence (1)

- MikhailGorbachev (2)

- Military (72)

- military dictator (1)

- Militaryplanes (5)

- militaryrecruitment (1)

- milledrice (5)

- Milli (1)

- Minassian (1)

- MinAungHlaing (2)

- miner (1)

- Mineski (1)

- MineskiGlobal (1)

- minesniffingdog (1)

- MINI (1)

- MINICooper (1)

- MINICooperElectric (1)

- Minimumwage (4)

- mining (3)

- Miningsector (1)

- MINIOne (1)

- MINIOneFrozen (1)

- MINIOneFrozenBrassEdition (1)

- minister (4)

- MinistryofEducation (1)

- MinistryofForeignAffairs (2)

- MinistryofPublicWorks (1)

- minor (1)

- misinformation (1)

- Miss Universe (1)

- missile (15)

- MissileLaunch (10)

- missiles (76)

- missilesystem (1)

- missiletest (12)

- Missing (18)

- missingplane (1)

- MissUniverse (3)

- MissUniverseOrganization (1)

- mitchmcconnell (1)

- mixedmartial (1)

- mixedmartialarts (2)

- MMA (1)

- Mobileapps (1)

- mobilebanking (1)

- mobilepayment (1)

- Models (1)

- Moderna (14)

- Modi (1)

- ModiDocumentary (1)

- MohammadQasemRazawi (1)

- Mohammed (1)

- MohammedbinSalman (2)

- Moldova (1)

- Molnupiravir (3)

- Monaco (1)

- MonaLisa (1)

- Mondul kiri (1)

- Mondulkiri (12)

- MonetaryPolicy (1)

- Money (18)

- moneylaundering (6)

- Mongolia (1)

- monk (2)

- monkeypox (26)

- monkeypoxinfection (1)

- monkeypoxoutbreak (1)

- monkinThai (1)

- Monsoon (1)

- Moody (2)

- Moon (5)

- moonbuggy (1)

- MoonJaeIn (1)

- moonsoil (1)

- MorodokTechoNationalStadium (1)

- mortarshell (1)

- Moscow (16)

- Moskva (4)

- Moskvawarship (2)

- Mosques (2)

- Mothers (1)

- motorbikeassembly (1)

- motorcyclemarket (1)

- motorcyclemarketinCambodia (1)

- Motorcycles (1)

- Motorola (1)

- mountains (5)

- MountEverest (4)

- Movie (13)

- movies (3)

- MPWT (1)

- mRNA (4)

- mRNAvaccines (1)

- MS804 (1)

- MSMEsinCambodia (1)

- MsPuiyi (1)

- MTStrovolos (1)

- multipurposespecialeconomiczone (1)

- mumbai (2)

- mummy (1)

- murder (2)

- Murder Mans laughter (1)

- MurderManslaughter (42)

- Museumsgalleries (5)

- Music (7)

- musicfestivals (1)

- Musk (1)

- Muslim (1)

- Muslims (10)

- Myanmar (102)

- Myanmarjunta (3)

- Myanmarprison (1)

- mysteriousliverdisease (1)

- mysterymissing (1)

- Nagaenthran (1)

- Nagasaki (1)

- names (1)

- Nancy (1)

- NancyPelosi (11)

- Nanmadol (2)

- Nanotechnology (1)

- Naomi (1)

- NarendraModi (9)

- NaroSpaceCentre (1)

- Naruhito (1)

- NASA (14)

- National (465)

- National Bank of Cambodia (1)

- NationalBankofCambodia (6)

- NationalGuardoftheUnitedStates (1)

- Nationalmonuments (1)

- NationalService (1)

- NationalStadium (1)

- NATO (42)

- Natural Disasters (3)

- NaturalDisasters (69)

- naturalgas (3)

- naturalgassituation (1)

- naturalgassupplies (1)

- nature (6)

- Naver (1)

- NAYPYITAW (1)

- nazi (2)

- NBA (2)

- NBC (5)

- NeakOkhnaKithMeng (1)

- NeakOknhaKithMeng (2)

- NeakPoan (1)

- NegligentactNegligence (1)

- Neighbours (2)

- NelsonMandela (1)

- Nepal (14)

- Nepalplanecrash (1)

- Neptune (1)

- Nesquik (1)

- Nestle (2)

- Netflix (5)

- Netherlands (3)

- networkinCambodia (1)

- new Covid variant (1)

- New Covid-19 (1)

- new Covid-19 variant (1)

- new delhi (1)

- New Zealand (4)

- newdelhi (1)

- newspapers (1)

- NewtGingrich (1)

- NewYearsDay (2)

- NEWYORK (12)

- NewYorkattack (1)

- NewZealand (24)

- neymar (3)

- NgocBinh (1)

- NgonSaing (1)

- NgornSaing (1)

- NGOs (4)

- Nham24 (1)

- Nigeria (4)

- nightactivities (1)

- nightclub (2)

- nike (1)

- Nissan (1)

- Nobell aureates (1)

- Nobellaureates (1)

- NobelPeacePrize (4)

- noflyzone (1)

- nojoke (1)

- NordStream (3)

- NordStreampipeline (1)

- Norodom Ranariddh (1)

- NorodomSihamoni (1)

- NORTH KOREA (2)

- NorthAtlanticTreatyOrganization (1)

- NorthKorea (171)

- NorthKorean (2)

- NorthKoreanuclear (1)

- Noru (1)

- norway (4)

- NotreDame (1)

- Novavax (1)

- NualphanLamsam (1)

- nuclear (17)

- NuclearAttack (3)

- nuclearcops (1)

- Nuclearenergy (10)

- nuclearplant (1)

- nuclearpower (2)

- NuclearPowerPlant (7)

- nucleartest (5)

- Nuclearwar (2)

- nuclearwarfare (1)

- nuclearweapon (5)

- nuclearweapons (66)

- nude (2)

- nudephoto (1)

- numberplate (1)

- Nuri (1)

- nutrition (1)

- Nutritionanddiet (2)

- Oakwood (1)

- OakwoodPremier (1)

- OakwoodPremierPhnomPenh (1)

- Obama (1)

- obesity (2)

- Obituary (2)

- obscenematerial (1)

- obscenephotos (2)

- OCA (1)

- Oceans (4)

- OCIC (1)

- OddarMeanchey (4)

- Odinga (1)

- office (2)

- Oil (2)

- oilandgas (14)

- Oilandgassector (3)

- oilembargo (1)

- oilimports (2)

- oilmarket (1)

- oilprice (1)

- Oilprices (2)

- OilpricesCrudeoil (11)

- Oilspills (4)

- oldestperson (1)

- oldestpersonintheworld (1)

- OLFootballClub (1)

- OLGroup (1)

- oligarch (4)

- Olympics (15)

- omicron (85)

- Omicron Covid-19 variant (1)

- Omicron variant (38)

- Omicronsubvariant (1)

- OmicronXE (1)

- OneLove (1)

- onlineinfluencers (2)

- OnlineShopping (2)

- OnlyFans (2)

- Oozing (1)

- opec (1)

- Opel (1)

- OpelZafira (1)

- OpelZafiraeLife (1)

- OpenAI (1)

- Opennet (1)

- Optus (2)

- OrgandonationTransplants (1)

- organicfood (1)

- organicstrawberries (1)

- OrientalBank (2)

- Osaka (2)

- OsakaWorldExpo (1)

- OsamabinLaden (1)

- Osechkin (1)

- OtavaoWaterfall (1)

- otherchildren (1)

- OutbreaksandEpidemics (11)

- OutrageofmodestyInsultingmodesty (1)

- OVSCambodia (1)

- OxPay (1)

- Pablo Kang (1)

- Pacquiao (1)

- Paetongtarn (1)

- Pailin (7)

- PailinLongan (2)

- Paintings (3)

- Pakistan (40)

- Pakistanflooding (1)

- Pakistani (2)

- Palaeontology (1)

- Palestine (6)

- Palestinians (2)

- palm oil (1)

- palmoil (12)

- palmoilexports (1)

- palmoilproducer (1)

- PalmSugar (1)

- panda (1)

- pandemic (20)

- pandemicfund (1)

- Pandemics (5)

- PanSorasak (2)

- PapuaNewGuinea (1)

- ParagAgrawal (1)

- ParalympicGames (1)

- Paralympics (2)

- parenting (3)

- parents (2)

- Paris (11)

- Parking (1)

- parliament (18)

- ParvatiValley (1)

- PAS (1)

- PassApp (1)

- Passport (1)

- pathogens (1)

- patient (2)

- patients (1)

- PaulWhelan (1)

- pawnshop (1)

- Paxlovid (5)

- Payment (1)

- PaymentinCambodia (1)

- peacetalk (2)

- PediaSure (1)

- Pele (6)

- Pelosi (1)

- PennSovicheat (2)

- pentagon (4)

- penthouse (1)

- Pepper (1)

- Pepper from Cambodia (1)

- pepperexport (1)

- performance (1)

- Performingarts (1)

- personalstories (1)

- peru (3)

- Pestech (2)

- PESTECH Cambodia (1)

- petitions (2)

- Petrolprices (1)

- Pets (5)

- Pfizer (19)

- Pfizerpill (1)

- PhanYingTong (1)

- Pharmaceutical (4)

- PHARMACEUTICALS (2)

- Philippine (1)

- Philippine presidential (1)

- Philippinedictator (1)

- Philippineferryfire (1)

- PhilippinePresident (1)

- Philippinepresidential (1)

- PHILIPPINES (84)

- Philippines election 2016 (1)

- PhilippinesPresidentialElection (2)

- Philips (1)

- Phnom Penh (39)

- Phnom Penh flights (1)

- Phnom Penh Post Office Square (1)

- Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone (2)

- PhnomPenh (118)

- PhnomPenhAutonomousPort (1)

- PhnomPenhBavet (4)

- PhnomPenhBavetexpressway (2)

- PhnomPenhBeijingdirectflight (1)

- PhnomPenhSEZ (2)

- PhnomPenhSihanoukvilleExpressway (2)

- PhnomPenhSpecialEconomicZone (3)

- PhnomPenhtoKoSamui (1)

- phosphorusbomb (1)

- photography (1)

- Phu Quoc (1)

- Phuket (1)

- PhuQuoc (2)

- PhuQuocisland (1)

- pigbusiness (1)

- pigeon (1)

- Pigs (2)

- pilgrims (1)

- Pinduoduo (1)

- PiPay (1)

- Pita (1)

- PitaLimjaroenrat (1)

- PLA (1)

- Placenta (1)

- PlaneCrash (9)

- planemissing (1)

- planescollided (1)

- planet (2)

- plants (2)

- Plastics (2)

- plasticwaste (1)

- PlasticWasteManagement (1)

- PlayStore (1)

- Plumereau (1)

- poaching (1)

- Podcast (1)

- pointofsale (1)

- Poipet (3)

- poisoning (5)

- Pokemon (1)

- poland (9)

- police (38)

- Policeraids (3)

- polio (1)

- Political (14)

- politicians (70)

- Politics (546)

- Politics and Government (8)

- PoliticsandGovernment (200)

- polls (4)

- Pollution (11)

- Ponzischemes (1)

- poorworker (1)

- popcorn (1)

- pope (6)

- PopeBenedict (2)

- PopeBenedictXVI (1)

- PopeFrancis (12)

- populationcrisis (1)

- PopulationDemographics (4)

- porn (2)

- Pornactor (1)

- pornatwork (1)

- Pornhub (1)

- porninparliament (1)

- Pornmoniroth (2)

- pornography (4)

- Porsche (1)

- PorscheTaycan (1)

- portinCambodia (1)

- portinKampot (2)

- Portugal (3)

- POS (1)

- Post Office Square (1)

- poverty (6)

- powder (1)

- powercostinCambodia (1)

- powerplant (1)

- powerplantinCambodia (1)

- Powerplants (8)

- PPSEZ (2)

- Prabowo (1)

- PrakSokhonn (3)

- pranks (2)

- PRASAC (1)

- PRASACMicrofinance (1)

- Prayut Chan O Cha (1)

- PrayutChanOCha (8)

- Prayuth (3)

- PrayuthChanocha (2)

- Preah Sihanouk (16)

- Preah Sihanouk Province (1)

- Preah Sihanouk Special Economic Zone (1)

- PreahSihanouk (25)

- PreahSihanoukmasterplan (1)

- PreahVihear (9)

- Predictions (1)

- Pregnancies (2)

- pregnancy (4)

- PregnancyParenting (3)

- PremierLeague (1)

- President Election (1)

- President Rodrigo Duterte (2)

- PresidentElection (2)

- presidential candidates (1)

- Presidential election (1)

- presidentialcandidates (2)

- Presidentialelection (18)

- PresidentRodrigoDuterte (1)

- Pressfreedom (6)

- Prey Veng (1)

- PreyVeng (6)

- Pricing (2)

- Pride (1)

- priest (1)

- Primaryschool (2)

- Prime Minister (3)

- PrimeMinister (59)

- PrimeMinistersOffice (1)

- Prince Norodom Ranariddh (1)

- PrinceAlbert (1)

- PrinceAndrew (3)

- PrinceBank (2)

- PrinceCharles (12)

- PrinceHarry (20)

- PrinceHarryDukeofSussex (3)

- PrincePhilipDukeofEdinburgh (1)

- Princess (4)

- Princess Aiko (1)

- Princess Mako (1)

- PrincessAiko (1)

- PrincessCharlene (1)

- PrincessCharlotte (1)

- PrincessDiana (8)

- PrincessofWales (2)

- PrinceWilliam (14)

- PrinceWilliamDukeofCambridge (2)

- PrinnPanitchpakdi (2)

- Prison (11)

- prisoner (6)

- PrisonerofWar (1)

- Privacyissues (6)

- PrivateJetservice (1)

- PrivateJetserviceinCambodia (1)

- processedcashewnuts (1)

- processingfactoryinCambodia (1)

- Productsafety (1)

- productsfromCambodia (1)

- Profiles (1)

- projectinCambodia (2)

- projects in Cambodia (1)

- property (3)

- propertycasualty (1)

- PROPERTYINVESTMENTS (1)

- Propertymarketsector (1)

- protection (1)

- protest (1)

- protests (69)

- PTT Cambodia (1)

- publichealth (1)

- Publichealthandhygiene (6)

- publicholidays (1)

- Publichousing (1)

- publicnuisance (2)

- PublicTransport (3)

- Publishing (1)

- PungKheavSe (1)

- Pungsan (1)

- Pursat (12)

- Putin (21)

- Pyongyang (2)

- pyramidschemes (1)

- QAnon (1)

- Qantas (2)

- Qatar (12)

- Qatar2022 (1)

- QianKeming (1)

- QRcodepayment (1)

- Quad (1)

- QuadSummit (2)

- quantum (1)

- Quarantine (1)

- Queen (5)

- QueenCamilla (1)

- QueenConsort (2)

- QueenConsortCamilla (1)

- QueenElizabeth (31)

- QueenElizabethII (21)

- R8V10 (1)

- RabbitIsland (1)

- Raceissues (2)

- racialdiscrimination (5)

- RadiationExposure (2)

- Radio (4)

- RafflesLeRoyal (1)

- RahulGandhi (4)

- RailwayCambodia (1)

- Railways (1)

- railwaysinCambodia (1)

- railwaysystemsinPhnomPenh (1)

- rainfall (1)

- Rajapaksa (2)

- Rajapaksas (1)

- rally (1)

- ramadan (2)

- Ramadanbombing (1)

- RamosHorta (2)

- rampage (1)

- RandPaul (1)

- RanilWickremesinghe (1)

- Rape (12)

- Rapid Sun (1)

- rapper (2)

- Rare earth elements (1)

- Ratanakiri (1)

- rathepatitis (1)

- RCEP (8)

- Realestate (2)

- realestateagency (1)

- RealMadrid (2)

- recall (3)

- Recycling (3)

- redbull (1)

- redcarpet (1)

- RedCross (1)

- RedSea (1)

- refugee (3)

- refugees (16)

- Refugees and Asylum seekers (2)

- RefugeesandAsylumseekers (9)

- regulationstoenterThailand (1)

- reinfection (1)

- Religion (15)

- religious (1)

- remdesivir (1)

- Remove (1)

- Ren Zhengfei (1)

- Renaissance (1)

- Renaissance Minerals Cambodia Limited (1)

- Renewableenergy (2)

- renminbi (1)

- Rental (2)

- ReportersWithoutBorders (1)

- Rescue (23)

- research (10)

- ResortsinKep (1)

- restaurant (2)

- restriction (1)

- retirement (3)

- Reuters (2)

- RHBBank (2)

- RHBBankCambodia (1)

- rhinos (1)

- RiaMoney (1)

- Rice (3)

- riceexport (1)

- ricefarmer (1)

- RiceimportfromCambodia (1)

- riceinCambodia (1)

- Riceprice (1)

- richestman (1)

- ridehailing (1)

- ridehailingserviceinCambodia (1)

- Ridehailingservices (1)

- Rielbanknotes (1)

- Rioting (11)

- RisenEnergy (1)

- RishiSunak (2)

- Riskmanagement (1)

- Rivers (1)

- RMA (1)

- RMAAutomotive (1)

- RMACambodia (1)

- RMB (1)

- RMKHGlove (1)

- RMSTitanic (1)

- Roadrage (1)

- roadsafety (4)

- Robbery (2)

- RobertTsao (1)

- Robotic (1)

- Robotics (2)

- robots (1)

- Robredo (1)

- Rodrigo Duterte (1)

- RodrigoDuterte (8)

- Rohingya (13)

- RolfHarris (1)

- RomanAbramovich (2)

- Romanchenko (1)

- Ronaldo (3)

- rouble (1)

- Royal Families (1)

- RoyalFamilies (10)

- RoyalGroup (7)

- royalinsult (1)

- RoyalRailway (2)

- RoyalRailwayCambodia (1)

- royalty (15)

- RSF (1)

- rubber (5)

- rubbercultivation (1)

- Rubberexport (1)

- RubberexportsfromCambodia (1)

- rubberwood (1)

- ruble (1)

- Rugby (2)

- RushHour2 (1)

- Russia (549)

- Russiacafe (1)

- Russiaeconomy (1)

- Russian (1)

- Russianbank (1)

- Russianbillionaire (1)

- Russianchessplayer (1)

- Russianenergy (3)

- Russiangas (3)

- Russianmoneylaundering (1)

- Russianoil (4)

- Russianoligarch (1)

- RussianPresident (2)

- Russiansanction (1)

- Russianwarsymbol (1)

- Russiaoil (2)

- Russiasanctions (1)

- RussiaUkraine (39)

- RussiaUkraineconflict (376)

- RussiawarinUkraine (30)

- RyanCoogler (1)

- Safety (9)

- Safi (1)

- sailing (1)

- Sailun (2)

- Sake (1)

- salaries (3)

- Salary (3)

- salarytax (1)

- sales (1)

- salmon (1)

- salt (2)

- Salt Bae (1)

- SalvaKiir (1)

- samesex (2)

- samesexcouples (1)

- SameSexMarriage (2)

- Samsung (6)

- SamsungCT (1)

- sanction (8)

- sanctions (2)

- Sandcrisis (1)

- SanFrancisco (2)

- SannaMarin (1)

- Santa Claus (1)

- SantaClaus (1)

- Saqqara (1)

- SARS (1)

- SARSCoV2 (2)

- Satellites (17)

- SaudiArabia (8)

- Savings (1)

- Scaloni (1)

- scams (8)

- scandal (3)

- SchoolClosures (1)

- schoolmassacre (1)

- schools (5)

- Science (97)

- scientificresearch (5)

- Scoot (1)

- Scootflight (1)

- Scotland (5)

- Scotlandindependence (1)

- ScottMorrison (5)

- SDBiosensor (1)

- seafood (1)

- SEAGames (2)

- Seagrass (1)

- SeangThay (1)

- seaport (1)

- seaturtle (1)

- seaurchins (1)

- secondShenzhencity (1)

- SecretServiceagent (1)

- selfdriving (1)

- Selfdrivingvehicles (3)

- Semeru (1)

- Semiconductor (6)

- Senegal (1)

- Seniorcitizens (3)

- seoul (16)

- Seoulstampede (1)

- SeparationsandAnnulments (1)

- Serbia (1)

- SerenaWilliams (1)

- SergeiShipov (1)

- SergeyKarjakin (1)

- SergeyLavrov (1)

- SerieA (1)

- serviceinCambodia (1)

- Serviceoutage (2)

- SevereWeather (2)

- sex (2)

- sexban (1)

- SexCrimes (1)

- Sexism (1)

- Sexoffences (2)

- sexoffender (1)

- sexscandal (1)

- sexslave (1)

- sextrafficking (2)

- Sexual Harassment (1)

- SexualAbuse (4)

- SexualAssault (9)

- SexualHarassment (4)

- Sexuality (1)

- sexualviolence (1)

- SEZ (3)

- Shanghai (6)

- ShanghaiCOVID (1)

- ShangriLa (2)

- ShangriLaDialogue (1)

- SHANTI (1)

- SharkBay (1)

- Sherman (1)

- SherylSandberg (1)

- Shinawatra (2)

- Shinsei Bank (1)

- ShinseiBank (1)

- ShintaManiWild (1)

- ShinzoAbe (18)

- Shionogi (1)

- ships (4)

- shipwreck (3)

- shoeimport (1)

- shoes (1)

- ShoesandSneakers (1)

- Shooting (17)

- Shooting Gun crime (1)

- ShootingGuncrime (46)

- shootinglessons (1)

- Shootings (1)

- shopping (4)

- shottodeath (1)

- showalltags (16)

- shows (1)

- SiamMakro (1)

- siblings (1)

- Siem Reap (10)

- SiemReap (45)

- SiemReapAirport (1)

- SiemReapAngkor (2)

- SiemReapAngkorInternationalAirport (5)

- SiemReapInternationalAirport (1)

- SiemReaproute (1)

- SiewPuiYi (1)

- Sihanoukville (9)

- Sihanoukville multi purpose Special Economic Zone (1)

- Sihanoukville port (1)

- Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone (1)

- SihanoukvilleAutonomousPort (5)

- Sihanoukvillemasterplan (1)

- Sihanoukvilleport (1)

- SihanoukvilleSpecialEconomicZone (2)

- SiliconValley (1)

- Singapore (32)

- Singapore Airlines (1)

- Singaporeexecutesmentally (1)

- SingaporeFoodAgencySFA (1)

- Singaporefootball (1)

- SingaporeNationalOlympicCouncil (1)

- Singaporepolitics (1)

- Singaporesports (1)

- singer (2)

- Singtel (2)

- sinkhole (1)

- Sinopharm (1)

- Sinovac (1)

- SisterAndré (1)

- skater (2)

- SkillsTraining (1)

- skin (2)

- Sleep (1)

- sleepingpill (1)

- Smart (1)

- SmartAxiata (1)

- smartphone (1)

- smartphonecontrols (1)

- smartphones (3)

- SMEBank (1)

- SMEs in Cambodia (2)

- SMEsinCambodia (1)

- smog (1)

- smoking (4)

- smuggling (3)

- snacks (1)

- snow (1)

- snowstorms (2)

- Soccer (4)

- soccerstampede (1)

- sochi (1)

- Social (1)

- Social media (1)

- socialdistancing (2)

- Socialmedia (50)

- socialmediainfluencer (1)

- Socialwork (1)

- Software (1)

- SohailAhmadi (1)

- SokChendaSophea (2)

- Solar (1)

- Solarenergy (1)

- solarpower (2)

- Solarproduct (1)

- Soldiers (9)

- Somalia (3)

- SongSaran (1)

- SoniaGandhi (1)

- Sorasak (1)

- South africa (3)

- South African (1)

- South east asia (1)

- South Korea (7)

- South Korean military dictator (1)

- Southafrica (7)

- SouthChinaSea (15)

- SouthChinaSeamap (1)

- Southeastasia (9)

- SoutheastAsian (2)

- SouthKorea (221)

- SouthKorean (1)

- SouthKoreanairforce (1)

- SouthKoreaStampede (2)

- SouthKoreatragedy (1)

- SouthSudan (2)

- Sovicheat (1)

- Soviet (1)

- SovietVictoryDay (1)

- space (20)

- Spaceandcosmos (7)

- spaceexploration (11)

- spacerocket (2)

- Spaceship (1)

- Spacewalk (1)

- SpaceX (14)

- Spain (15)

- Spanish (1)

- Special economic zone (2)

- Special Economic Zone in Cambodia (1)

- speech (3)

- Sports (144)

- Sportsandrecreation (1)

- SportsCar (1)

- SportVillage (1)

- spying (13)

- spyware (1)

- SQ5 (1)

- Sri Lanka (2)

- SriLanka (34)

- SsangYong (1)

- SSEZ (2)

- stabbing (5)

- Stabbings (1)

- Stablecoin (1)

- Stalker (3)

- stampdutytax (1)

- stampede (10)

- stampedeinYemen (1)

- Starbucks (1)

- Starlinks (1)

- Startup Cambodia (2)

- Startups (2)

- StateCourts (1)

- statue (4)

- stealing (1)

- SteveJobs (1)

- StockMarket (1)

- stocks (2)

- StocksandShares (4)

- store (1)

- Storm (1)

- StrategicAlliance (1)

- strawberries (1)

- streaming (1)

- StreamingMusicVideoContent (2)

- StreamingVideoContent (1)

- Strike (1)

- strikes (8)

- Strovolos (1)

- Students (9)

- study (18)

- StungTreng (3)

- Subaru (1)

- submarinefiberoptic (1)

- subway (1)

- subwayattack (1)

- Sudan (2)

- SugarRayLeonard (1)

- Suicide (1)

- Suicidebombing (1)

- Suicidedrone (1)

- Suicides (8)

- Sumatra (1)

- Sumatraisland (1)

- Sumitomo (1)

- SumitomoWiring (1)

- Sun Chanthol (1)

- Sunak (1)

- SunChanthol (4)

- SupachaiPanitchpakdi (2)

- supermarkets (1)

- supernatural (1)

- superstition (1)

- superyacht (2)

- supply chain (1)

- supplychain (12)

- surveillance (5)

- Surveys (1)

- survivorstories (1)

- sushi (2)

- suspended (1)

- Sustainability (4)

- SuuKyi (1)

- SUV (1)

- SuzukiCup (1)

- SvantePaabo (1)

- Svay Rieng (2)

- SvayRieng (14)

- SWEDEN (5)

- Swift (2)

- swiftletnest (1)

- Swimming (1)

- Swineflu (1)

- SwireCocaCola (1)

- SwirePacific (1)

- Switzerland (3)

- Sydney (6)

- Syria (8)

- TADA (1)

- Tade (1)

- Taekwondo (1)

- TaikiYanagida (1)

- Taipei (1)

- Taiwan (170)

- Taiwaneseartiste (1)

- Taiwanjets (2)

- Taiwanreunification (1)

- TaiwanStrait (1)

- TalebanTaliban (12)

- talentcompetitiveness (1)

- taliban (2)

- Talibanforces (3)

- Talibangovernment (1)

- Talibanpolice (1)

- TanKakKhun (1)

- Tanzania (1)

- Taoist (1)

- TaProhm (1)

- TaProhmtemple (1)

- tariffsonChineseimport (1)

- tattoo (1)

- tattoos (1)

- Tax (4)

- taxinCambodia (1)

- Taycan (1)

- Tboung Khmum (1)

- TboungKhmum (1)

- TCMTraditionalChineseMedicine (1)

- TCross (1)

- tea (1)

- TeaBanh (1)

- Teachers (2)

- Tech (152)

- TechnologyinCambodia (1)

- Technologysector (1)

- Techo Startup Center (1)

- TechoInternationalAirport (2)

- Teenagers (7)

- Tehran (1)

- Telcos (1)

- telecom (1)

- Telecommunication (1)

- telecomsnetworkinCambodia (1)

- Televangelist (1)

- Television (1)

- Temasek (1)

- Temasekholdings (1)

- tennessee (1)

- Territorialdisputes (8)

- terrorism (20)

- terrorists (1)

- terroristthreat (2)

- Tesla (22)

- testing (1)

- TetsuyaYamagami (1)

- Texasmassacre (2)

- THAAD (1)

- Thai (2)

- Thai junta (1)

- ThaiAirways (2)

- Thaicannabis (1)

- Thaieconomy (1)

- Thaielephant (1)

- Thaifood (3)

- Thaijunta (2)

- thaiking (3)

- Thailand (150)

- ThailandBanking (1)

- ThailandPass (1)

- ThailandtoCambodia (1)

- Thaimilitary (3)

- Thaimonk (1)

- ThaiPM (2)

- Thaipolicemen (1)

- Thaipolitician (1)

- Thaipolitics (13)

- Thairebels (1)

- ThaiSmile (1)

- Thaitemple (1)

- Thaitransgender (1)

- Thaksin (2)

- ThaksinShinawatra (2)

- Thawee (1)

- TheatrePlays (1)

- TheftBurglary (2)

- TheGreatBarrierReef (1)

- ThePentagon (1)

- Theranos (1)

- therapeutics (1)

- theroyalfamily (1)

- ThichNhatHanh (1)

- TiananmenSquare (2)

- Tiangong (1)

- Tibet (1)

- ticketfraud (1)

- TikTok (23)

- TikTokinfluencer (1)

- TikTokvideo (1)

- TimorLeste (6)

- Tirefactory (2)

- TirefactoryinCambodia (2)

- tiremaker (1)

- TireplantinCambodia (1)

- Titanic (1)

- ToanChet (1)

- tobacco (2)

- Tokopedia (1)

- TOKYO (11)

- Tokyostadium (1)

- TomParker (1)

- TomParkerdies (1)

- Tonga (1)

- Tonsay (1)

- Tonsayisland (1)

- Total (1)

- TotalEnergies (3)

- TotalEren (1)

- TottenhamHotspur (1)

- tour (2)

- tourism (37)

- Tourism61450 (1)

- Touristattractions (4)

- tourists (12)

- Toyota (10)

- ToyotabZ4X (1)

- ToyotaCambodia (1)

- ToyotaCorolla (1)

- ToyotaCorollaCross (1)

- TPPTransPacificPartnership (1)

- trade (10)

- trademarkIntellectualproperty (1)

- Tradeunions (1)

- Traditional (3)

- traffic (2)

- TrafficCongestion (1)

- trafficjam (1)

- trafficjamsinIndonesia (1)

- Train (3)

- Transgender (8)

- Transportation (2)